“Gender violence did not start with a little boy mistreating a little girl. But with a man teaching punches and blood to his son. To make him understand that to have his place in the world he needs to be cruel, violent and abusive.”

Lydia Cacho, investigative journalist and rights activist, has listened to tales of abuse, torture, human trafficking and child pornography. She has collected the stories of the most vulnerable victims like few others dared to, risking her life to relentlessly fight violence against women and children.

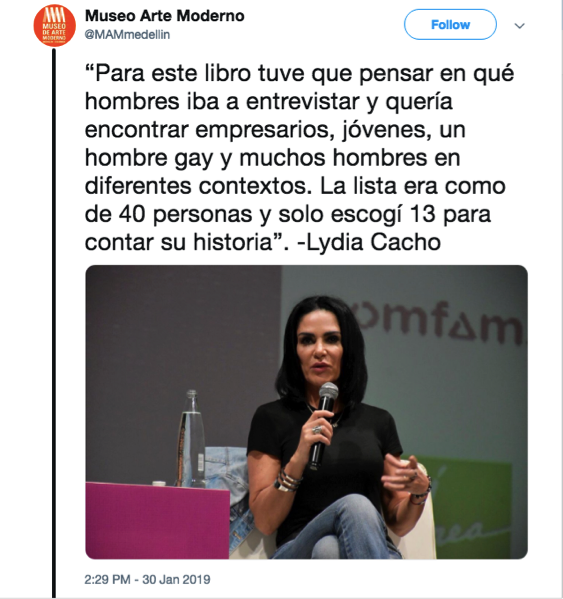

In contrast then, her latest endeavour may come at a surprise: In #EllosHablan, her new book she presented at this week’s Hay Festival in Medellin, she gives a voice to a panorama of ‘everyday’ boys and men. From the disadvantaged teenager to the successful adult businessman, she is determined to track the roots of violence down by asking them, for the first time, a seemingly simple question: “How did you learn what it means to be a man?”

Journalist and rights activist Lydia Cacho spoke at the Hay Festival Medellin about her new book, #EllosHablan, machismo and gender violence. Image courtesy: @MAMmedellin

The testimonials are profoundly personal, yet they share common threads. One man recounts how as a child he was violently beaten by his father, feeling “as much hate as a six-year old possible can feel”. But going to the bathroom to wash his face, he looked in the mirror and was struck with a sudden realization: “I am identical to Dad”.

This fundamental contradiction about identification with violent fathers, Cacho explained in her talk, is essential to understanding how violence is reproducing violence – from father to son, from generation to generation, and from the personal to the society.

And speaking to the Colombian audience in Medellín, she heavily criticizes the “mano duro” security paradigm that has made a reappearance in government discourse and policy through current Colombian President Duque. “Meeting violence with more violence”, she summarizes ‘mano duro’ as echoing the same principle.

Much Ado about Masculinity

“We think that Women have fears, but they cannot compare to the fears of men”, says Cacho about one of the biggest surprises of her research. Men are constantly “afraid of being judged”, she believes, “by other men, by their father, by politicians, by criminals”, in short, by society.

Indeed, some social scientists argue that the driving force of ‘sexist’ or ‘stereotypical male’ behaviour is not always misogyny, but fear: Manhood, the argument goes is “fragile” in the sense that it cannot be taken for granted, it needs to be earned.

Men have a “chronic anxiety about their status, explains US researcher Jennifer Bossom in a recent social science podcast, and “that translates into a concern about whether one’s seen as a real man or not”.

In her research, she let men braide either rope or hair, the latter a stereotypical ‘feminine’ activity, and made sure they felt to be in the public spotlight. Next, they had two choices: A brain teaser puzzle – or put on some boxing gloves and hit a punching ball. A control group braided rope instead of hair. Her research was able to demonstrate that if men braided hair, they were much more likely to chose the punching task – to restore their ‘masculinity’ by acting aggressively, she argues.

The mechanisms of how violence becomes interwoven with masculinity, is this unique to Latin American Machismo? A question we asked Lydia Cacho at the Medellín Hay Festival. “My book represents all men in the world”, she replies, and points out that even in progressive states like Sweden and Finland gender violence continues to be a big problem.

Even after the global movement of #metoo and HeforShe, violence against women and girls continues to be a “global pandemic”, says the Wold Bank: More than 1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence.

What is the way forward? “The next big task for feminism is a movement of men”, believes Lydia Cacho. “We need marches of men who say ‘I am not machista’“.