Trauma, depression and rising suicides: Experts are warning of a public health emergency as surging violence is taking its toll on Mexico’s population. Yet few measures are taken to address a looming mental health crisis in the country.

A brief glimpse at the statistics of violence and insecurity in Mexico: Mexico’s murder rate reached a sad record in 2017, and is expected to rise even further. Los Cabos municipality recently surpassed Caracas as the city with the world’s highest murder rate with a staggering 11,133 homicides per 100.000 inhabitants, and three out of the five most dangerous cities of the world are located in Mexico. Behind these cold statistics, violence is certainly taking its toll on the lives and minds of Mexican citizens.

“40% of the population is paralyzed by insecurity”: Large red headlines of newspaper Unomásuno quote the bleak statement of Alfonso Romo, the likely candidate for future chief of office of the newly elected government, which was made last month. In a country torn by war-like levels of violence, measures to establish security and combat the continuous suffering of citizens has unsurprisingly reigned on the forefront in the recent race of governmental elections.

However, while the frequent news of murders, tortures and physical violence are shocking the nation, some less visible consequences are tearing on Mexico’s society: The mental health toll of witnessing years of extreme violence.

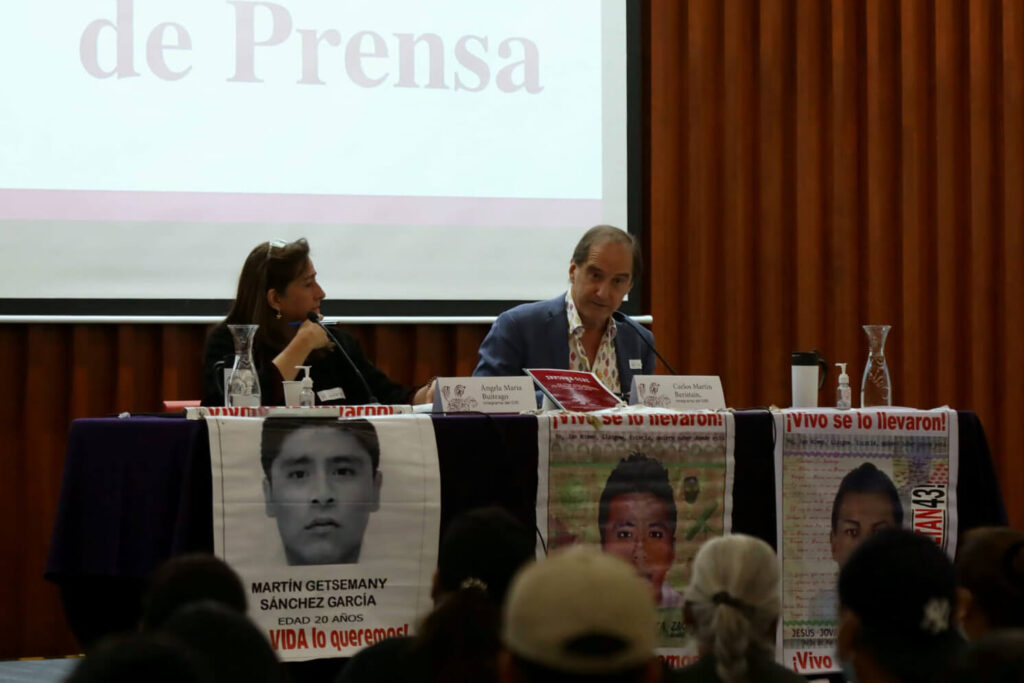

Indeed, those particularly exposed to violence report alarming rates of mental illness. More than three-quarter of journalists in Mexico suffer from high rates of anxiety and more than 40 percent report symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychologists from Mexico’s National Autonomous University found in a recent study.

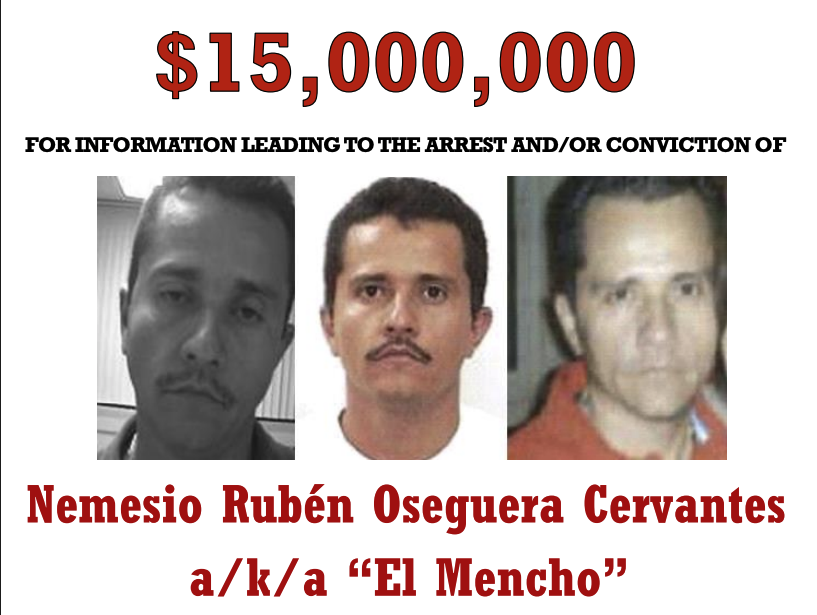

Furthermore, research points out that PTSD rates are significantly higher for journalists covering drug-related violence. In addition to having to cover acts of extreme brutality every day, journalists often have to fear for their own lives as Mexico is now considered one of the most dangerous parts for them to work.

Read more: Lydia Cacho, one of Mexico’s most threatened and most fearless voices

It is difficult to estimate precisely the overall prevalence of mental illness in Mexico. According to official statistics by the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 4% of Mexico’s population suffered from depression last year.

However, many psychologists point out that dark figures are likely to be much higher. For example, a study from Yale Global Health Review points to stigmas linked to ‘machismo’ beliefs such as ‘men cannot suffer from depression’ that lead to underreporting.

Chronic violence could explain rising suicides

The researchers also warn of popular misconceptions of mental health such as “what does not kill you makes you stronger”.

On the contrary, violence researcher

While overall suicide rates are still low – Mexico is No. 148 in global ranking – the national suicide rate has doubled between 1990 and 2015, according to country statistics. Furthermore, aggregated data hides how some groups are disproportionally affected, such as men under age 44.

Last year, Chihuahua saw 12.3 suicides per 100,000 residents – more than twice the Mexican national average. Ciudad Juarez has reemerged as one of Mexico’s most dangerous cities after a recent line of violent attacks.

Read more: AMLO heads to peace discussions in Ciudad Juárez amidst growing homicide rates

Taken on a national level, this case “may well indicate a simmering public health emergency in other Mexican states”, warns Farfán-Mendez.

Destroying the invisible “social fabric” of Mexico’s society

While suicide is one manifestation of the mental health danger generated by Mexico’s violence, other consequences remain less visible.

Experts from the World Bank warn that mental illness has not only significant impact on an individual level but also blocks the development of countries in Latin America. On a national level, absences from work related to mental illnesses such as depressions are significantly lowering overall productivity, the experts say.

In relation to violence and trauma, researchers warn that the impact is likely to run much deeper into the important social ties that hold Mexico’s society together.

“The social fabric is so destroyed that it cannot be healed in one generation or two,” says Elena Azaola from the Centre for Social Anthropology High Studies and Research in Mexico city about the mental health consequences of the soaring violence.

“No one pays attention to it. No one is aware of the aftermath, and no one can visualise its magnitude”, she adds.

Furthermore, many fear that violence reproduces itself in a vicious circle.

”In effect, violence generates violence. Many battering fathers were beaten children,” explains Juan Ramos de Fuente, Professor of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “It has also been scientifically documented that violence is imitated and infected. The frequent exposure to violent scenes in real or virtual life and the social resonance that it has are factors that predispose to violence.“

NGOs struggle to fill the void in public support

Few initiatives offer psychological support for victims of violence. Many of the most affected conflict areas have insufficient access to basic public health care, let alone trained psychologists or mental health workers. Many communities suffer from being remote, others from deteriorating security that renders the work of medical staff difficult to impossible.

Local and international NGOs are struggling to fill in the gaps in public service. “We only visit each community once a month because of the volatile context. Individual consultations can’t belong,” says Laura Moreno from Doctors without Borders (MSF). The NGO has been running more than 1,200 consultations in 2017 for victims of violence in the state of Guerrera, providing primary health care, mental health care and psychosocial activities.

“People in Guerrero are tough, but if the fear and violence persist, the fabric of society could be torn apart”, she echoes a common fear.

Despite this warning, public spending on mental illness is deemed insufficient to cover basic needs all over Latin America. In Mexico, only 2,2% of public health budgets are earmarked for mental health. Furthermore, mental health has long been recognized as one of the main unresolved issues within Mexico’s government’s health policy agenda, and no reforms are in sight.

On December 1st, all eyes in Mexico will turn to President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador taking office. Turning into reality election promises to curb violence is likely to be the acid test of the newly elected Mexican government. However, Mexico needs to address not only the salient issue of insecurity rippling through the country but also a crisis less visible: The psychological trauma and torn social fabric that years of extreme violence are creating.