Mexico City, Mexico — Since 2015 Chiapas has become a focal point of violence in Mexico, with clashes between different armed groups increasing sharply since 2021. Drug cartels, militias and paramilitary groups have scourged the once peaceful, southernmost state.

Sharing a border with Guatemala, Chiapas is known as a den of indigenous culture and is also home to the country’s largest biome, the Lacandon Forest. However, its rich farmland and strategic location have placed the state in the crosshairs of powerful criminal groups and international economic interests.

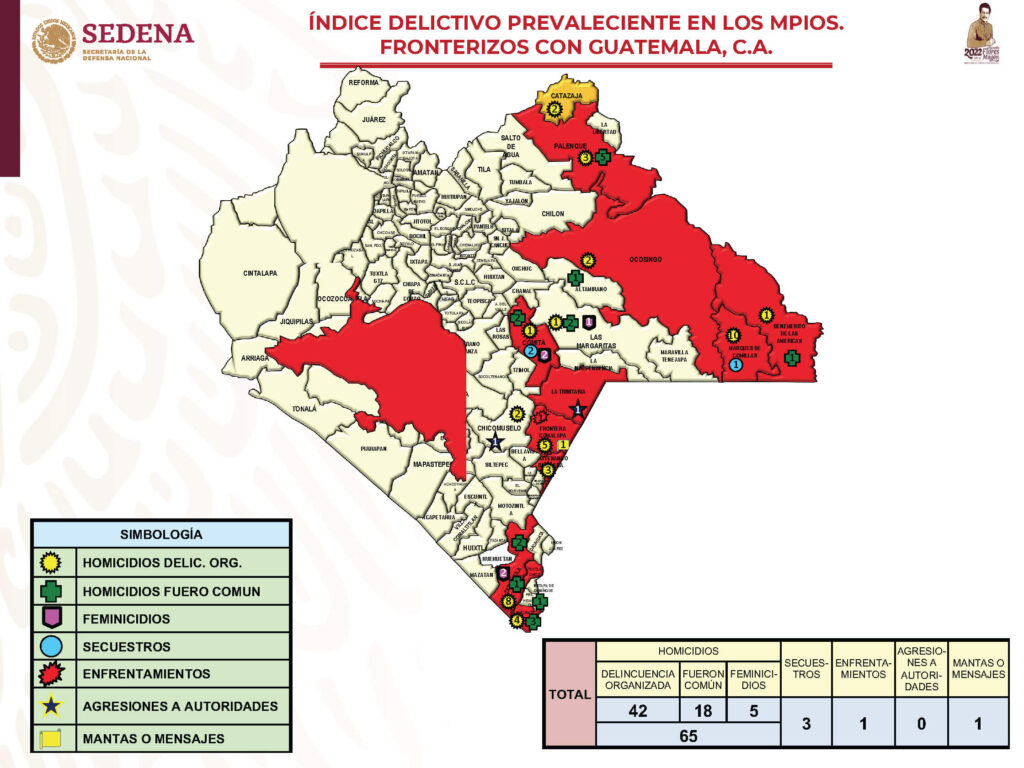

According to intelligence gathered by Mexico’s Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA), drug cartels exploit Chiapas’ proximity to the Central American drug trade, using the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean to smuggle drugs into Guatemala and establishing sea and land routes to penetrate the Mexican border.

Mainly, Mexican drug cartels have used its links to the Guatemalan criminal syndicates to smuggle fentanyl. The synthetic opioid is not produced in Guatemala. However, Mexican gangs established air and sea routes in Central America to export the drug internationally.

The presence of criminal interests in the state has disrupted the peace in Chiapas, increasing crime rates. Since 2015, the state has experienced a steadfast increase in homicides almost every year. However, while preliminary reports show a decrease in homicides of 13% compared to last year, disappearances in Chiapas have soared, reporting 849 disappearances in 2022, 45% of them of minors.

Chiapas currently ranks fourth in disappearances among Mexican states. In the first six months of this year, 492 people were reported missing in the state, of which 167 were women.

Northwest drug cartels head south

For years, Mexico’s most powerful drug cartels have moved hastily towards its southern border with Guatemala. Chiapas’ proximity to Central American drug and migrant smuggling gangs makes it a strategic location for cartels, according to organized crime watchdog Insight Crime.

Two of Mexico’s most prolific cartels, the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (CJNG), are warring for control of the border state, bringing ruthless violence similar to that which northern areas on the border with the United States experienced in prior cartel conflicts.

Carlos Ogaz heads the department of systematization and impact at the Fray Bartolome de las Casas Human Rights Center, an NGO established in 1989 that documents human rights abuses in Chiapas.

He told Aztec Reports that there’s been an uptick in criminal activity in the past decade.

“From 2015 to date, we have been experiencing a gradual increase in violence in the state; armed groups with great firepower, tactical equipment, and methods of terror linked to criminal groups – Sicarios – came to the fore,” said Ogaz.

“Dismemberment of people, beheadings … More and more we witnessed elements linked to the violence of organized crime,” he added.

While cartels have been active in Chiapas for two decades, the state’s most recent explosion of violence was reportedly sparked by the July 2021 assasination of Ramón Gilberto Rivera Beltrán, the son of local Sinaloa Cartel leader Gilberto “El Tío Gil” Rivera Amarillas, who is currently in prison in the U.S. The hit was presumed to be carried out by the CJNG.

According to leaked documents from SEDENA, Rivera’s murder fractured the Sinaloa Cartel in Chiapas.

“In the state of Chiapas, the [Sinaloa Cartel] is the one that currently maintains the hegemony of drug trafficking activities; However, the death of Ramón Gilberto Rivera Beltrán, El Junior, in July 2021, caused a leadership vacuum in the criminal group he headed, causing conflicts and differences between the cells that comprise it, considering a fracture inside the structure of the cartel,” read the SEDENA document dated June 2022.

At the same time, the CJNG has been gaining influence in the region.

An investigation by Guatemala’s Prosecutor’s Office for Drug Trafficking Crimes uncovered that criminal organizations there are collaborating with the CJNG as well the Guatemalan military to traffick cocaine, and in June, the CJNG reportedly kidnapped 16 agents from the Secretary of Security in Chiapas.

The cartel violence is spilling over into the civilian population.

By June, over 3,000 people from the border region in Chiapas had fled their homes. Reports of people being abducted, including children, added to the surge of mass migration.

According to Fray Bartolome de las Casas, the constant shootings, executions, and abductions in Chiapas reflect conditions seen in war zones.

But it’s not just cartel violence that is afflicting Chiapas. Homegrown militias and paramilitary groups — some supported by drug traffickers — have also gained strength in recent years.

These right-wing armed groups formed to protect private business interests in the region and to subdue indigenous and agrarian movements pursuing social justice and autonomy — namely the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), a guerrilla movement formed in 1983 which controls substantial territory in Chiapas.

“There are two fronts that form bridges and come together as if they were one,” said Ogaz, referring to the close relationship between drug cartels and paramilitary groups.

Counterinsurgency, private business and Mexico’s government

Since 1994, the Zapatistas have exercised influence and control over a large part of the territory of Chiapas. Since their uprising, they have created 43 rebel areas or Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ) — territories governed by communal boards that do not recognize the Mexican government.

Originally 27 rebel municipalities organized into five Zapatista territorial demarcations called “Caracoles,” the rebel group added 11 more territories in 2019 (for a total of 43 Zapatista zones), promoting communal government and economy and the self-determination of indigenous peoples.

Since declaring war on the Mexican state and its “neoliberal policies” in 1994, the Zapatistas have suffered violent attacks by paramilitary groups aligned with local business leaders and the federal government. And the violence has spilled over into the general population.

On December 22, 1997, paramilitaries stormed a prayer service in the town of Acteal, killing 45 Tzotzil Indigenous people including pregnant women and children. The prayer group was attended by members of the pacifist Las Abejas group, who had expressed their support for the Zapatista movement.

According to the Fray Bartolome de las Casas and other human rights organizations, paramilitary groups are still active in the region today.

One such group, the Cafeticultores de Ocosingo (Orcao), or Ocosingo Regional Organization of Coffee Growers in English, has reportedly carried out armed attacks against the Zapatistas in their territory in 2021, including burning their schools.

In May 2023, the Zapatistas denounced that the Orcao shot at Zaptista Jorge López Sántiz, an attack that left him gravely injured.

A month later, the Orcao allegedly coordinated armed attacks in three Zapatista communities: Emiliano Zapata, San Isidro, and Moises and Gandhi, all located in the official municipality of Ocosingo, Chiapas.

“What we are experiencing is the continuity of the counterinsurgency. [The paramilitaries] have links with organized crime because of their great firepower and population control tactics, such as roadblocks, and shortening supplies,” said Ogaz.

In June, the Zapatistas went as far as to say that the state is “on the verge of civil war.”

Read more: ‘On the verge of civil war’: Zapatistas march to demand peace in Southeastern Mexico

In addition to drug cartels, the Zapatistas also claim that paramilitaries are working in concert with local and national government officials.

Chiapas Governor Rutilio Escandón, a close ally of President President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and the brother-in-law of former Interior Minister Adan Augusto López, has been accused by the Zapatistas of protecting paramilitary groups operating in the region.

López Obrador’s government currently has two mega-projects being constructed in the state — Tren Maya and the Inter-Oceanic Corridor — which have directly impacted Indigenous and peasant communities in Chiapas.

The Zapatistas have accused López Obrador of turning a blind eye to the violence in Chiapas.

“Why does López Obrador keep silent?” asked the Zapatistas in a recent statement. “Because, like his predecessors, he can not tolerate that a rebel group can be a referent of hope and dignity. Because he needs to justify a military action to ‘cleanse’ the southeast and finally be able to impose his megaprojects.”