“Dónde están, dónde están, nuestros hijos ¿dónde están?”- “Where are they, where are they, where are our sons?” These calls, echoing through the hall of the University Tlatelolco where the incoming President Andrés Manuel López Obrador met with family members of disappeared people, made one message clear: Mexico’s population has enough of a crisis of violence that is spiralling out of control.

Much less clear, however, is the government recipe for lasting peace that citizens can expect when the new government headed by López Obrador, dubbed AMLO, will be sworn in December 1st. In a week that saw the latest dialogues on peace akin to the Tlateloco encounter cancelled after previous events were collapsing in protest, the main discourse of the incoming President is reconciliatory, trying to calm down citizens that refused to stay quiet even during the minutes of silence requested to commemorate victims. While concrete policy plans yet need to be revealed, their capacity ends this crisis of violence is clearly the first and most salient issue the new administration will face.

The scramble for solutions to end Mexico’s chronic violence has undoubtedly begun. But what could this new approach promoting peace in the country look like? We have been speaking to a team of Mexican and international researchers that were on the ground to answer this question.

Solving chronic violence is more than reducing murder rates

“It is not just about eliminating organized crime or criminal actors. It is about eliminating a situation where people are living in perpetual insecurity, a feeling of ‘something’s going to happen to me’ “, says Cecilia Farfan-Mendez, Researcher from the University of California and part of the research project ‘Co-constructing Human Security in Mexico’. To better understand how to address Mexico’s chronic violence, the team of researchers has connected with communities across age groups in four cities that have been disproportionately affected: Acapulco (Guerrero), Apatzingán (Michoacán), Guadalupe (Nuevo León) y Tijuana (Baja California).

One key lesson is drawn from the community discussion the researchers had with communities on the ground is that violence comes in plural form; meaning that victims of violence are not only reflected in rates of homicides.

Drug conflicts and mass graves that make it onto the news are clearly one form of violence, the researchers argue, but it is important to understand that the chronic violence plaguing Mexico’s population is also played in much less visible domains – such as domestic violence in people’s homes, or cultural violence of stigmatizations and prejudice.

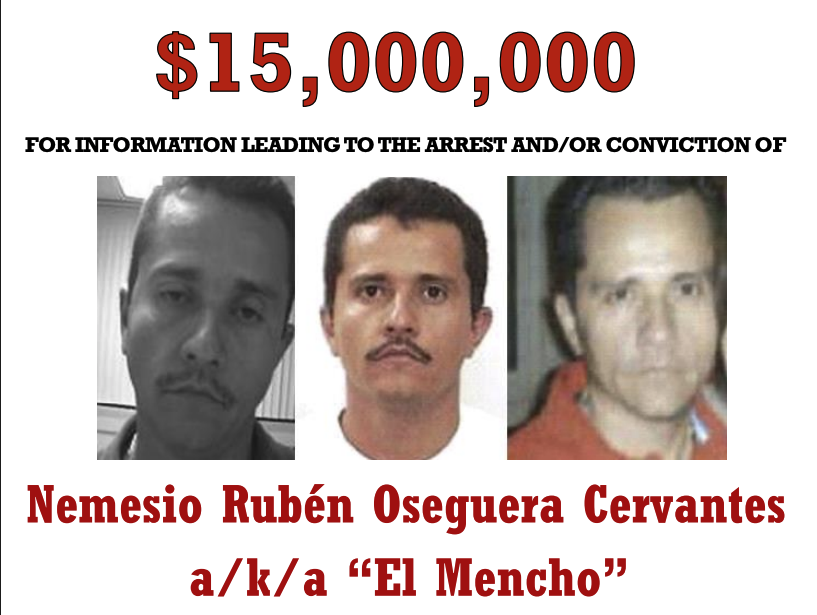

Why is it this nuanced understanding of violence important? “A lot of the explanations of violence are linked to drug trafficking”, says Farfan-Mendez. “They certainly have their role to play, but just focussing policy solutions on this aspect will not be enough”.

Building on a methodology originally developed by the Observatorio de Seguridad Humana of Medellín, Colombia, the main premise is that every community is differently affected by and responding to violence. For example, while domestic violence is generally associated with women being most at risk, instead one research group revealed the elderly population also to be afraid of violence in their homes.

The same is true for young people, who are rightly seen as a particularly vulnerable group: Just last week, the NGO Doctors Without Borders called on the Mexican government to improve access for mental health services for young people, warning about the effects of anxiety, depression and psychosis that living in the context of chronic violence creates. Globally, 50% of mental health illnesses begin before the age of 14 and suicide is the second cause of death between 15 and 29 years, according to the WHO.

However, as the research showed, violence towards young people is playing itself out in very different ways. In one of the cities, it is structural violence: Younger participants are seen “lost generation” without any access to economic opportunities. In another community, they reported to feel stigmatized by the community and the police as potential delinquents, discriminated against simply for being young and male.

“We really need to understand the complexities of each local context”, says Farfan-Mendez.

Furthermore, while the state is undoubtedly important to provide security, research on violence is highlighting that top-down approaches are not enough. “The state needs to incorporate communities that have been affected by violence into their policy designs.”

The deep scars created by judicial impunity

The vicious cycle of violence that keeps reproducing is often associated with unemployment, poverty and a general lack of economic opportunities. However, a very different factor may have an equally if not larger detrimental power to acerbate damages of chronic violence: Widespread judicial impunity.

Mexico ranks worst country in Latin America and fourth worldwide in the 2018 Global Impunity Index. “If impunity continues to worsen at the rate we’ve seen in recent years, it’s very likely we face the total collapse of both the security and justice system in our country”, commented the Dean of the University of the Americas Puebla (ULAP) on the presentation of these statistics earlier this year.

What’s more, reporting on impunity and corruption within the country has also become an increasingly dangerous area for journalists with Mexico now tallying the highest amount of media worker disappearances across the world.

Farfán-Mendez, an experienced violence researcher, says that even she was surprised at the magnitude of scars that impunity is creating for victims. “You may talk to participants of the research, victims who had awful things happening to them. But it is really impunity that really creates this sense of powerlessness, of no protection, that there’s nothing that can be done”, she explains.

Having no justice to turn to is not only traumatic of for individuals. At a larger scale, it may also affect the political choices of the society by creating a desire for vengeance that should not be underestimated.

“Because they feel so unprotected, people are calling on incarceration for life, or on the death penalty, or other measures most research agrees does not necessarily make you safer in the long run”, says Farfán-Mendez. Can impunity thus be creating political ‘hardliners’, such as more military interventions? Based on the anecdotal evidence from the research, this hypothesis can at least not be excluded.

The official rhetoric adopted by incoming President AMLO is so far very conciliatory, earning him harsh criticism of some in the population: “I do forgive and I can be at odds with some because of that. I say no to forgetting, yes to forgiving”, he stated in a recent peace forum.

So far, AMLO’s new administration seems to be determined to create a more bottom-up approach to chronic violence in Mexico, trying to forge citizen dialogue and refraining from a rhetoric akin to Felipe Calderon’s ‘War on Drugs’.

However, with the toxic mix of violence and impunity further tearing public trust, he might quickly be under pressure by groups that may demand a more hardline approach for security. With the countdown for the new government running, it can only be hoped that AMLO and team will resist populist top-down measures – and strive for a more nuanced, bottom-up and holistic approach towards building lasting human security in Mexico.