Mexico City, Mexico — Following a series of international court rulings, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador recently sparked a political debate over the Mexican Supreme Court’s obligation to enforce Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) rulings on the country’s use of pretrial detention.

The judicial mechanism allows a suspect to be jailed for up to two years, however, in practice, suspects have been imprisoned far longer, and it is estimated that 40% of the country’s prison population — or around 90,000 people — remain incarcerated without a conviction.

The IACHR ruled last year that Mexico’s use of pretrial detention runs counter to the American Convention, to which Mexico is a signatory. Because Mexico’s Constitution stipulates that it must adhere to international human rights conventions, the Supreme Court and Congress must abide by the ruling and nullify pretrial detentions.

The administration of López Obrador has recently pressured the Court to uphold pretrial detentions, labeling it a national security issue.

In April, Interior Secretary Luisa Alcalde warned that 68,000 “criminals” — including murderers, rapists and organized crime figures — would be let loose on the streets if pretrial detention was repealed. “We call on the Court to respect the Constitution, respect the division of powers, and not exceed its powers. We also ask that the Court consider the serious consequences that eliminating pretrial detention would have for national security in the current circumstances,” said Alcalde.

Human rights groups, however, claim the legal tool is repressive, disproportionately affects poor people, and contributes to the structural weaknesses within Mexico’s judiciary.

“It is the poorest people being held in pretrial detention,” Simón Hernández León, a lawyer and member of legal rights group Pena Sin Culpa (Penalty Without Guilt), told Aztec Reports. “It must be said, these people are innocent because they are being investigated and on trial, but they have not been convicted.”

León was involved in one of the most prominent recent cases which shed new light on the issue of pretrial detentions in Mexico. The case of Daniel García Rodriguéz.

17 years, 6 months, and 5 days in pretrial detention

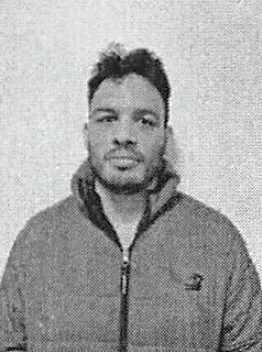

On February 25, 2002, Daniel García Rodriguéz, a secretary that worked in city hall for the municipality of Atizapá in the State of Mexico, was arrested along with another man, Reyes Alpízar Ortiz, for allegedly murdering city councilwoman María de los Ángeles Tamés.

The two suspects were originally put on house arrest, and later pretrial detention. According to court documents, they were subsequently held in pretrial detention for over 17 years before a judge released them in 2019. On May 12, 2022, a court convicted them for the murder and sentenced them to 35 years in prison — a verdict they appealed.

In April of 2023, The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) ruled that the Mexican State was “responsible for violating the right to personal integrity, right to personal liberty, right to judicial guarantees, right to equal protection of the law, and right to judicial protection” of García Rodríguez and Alpízar Ortiz.

The Court also ruled that the use of house arrest and pretrial detention in Mexico ran counter to the American Convention, to which Mexico is a signatory, and that during their detentions, García Rodríguez and Alpízar Ortiz were “subjected to coercion and torture, and these claims had not been not duly investigated by the State.” García Rodríguez has since been released from prison while he appeals his conviction, and Alpízar Ortiz was acquitted in April 2023.

“During that time, human rights did not exist, neither in the Constitution nor in my head,” García Rodríguez told Aztec Reports of the time he spent in detention. “No culpability whatsoever, without any judicial responsibility, people end up in jail simply because they are accused, harming, among many things, one’s family, children, and spouse.”

He said that the prosecution threatened him and his family. “[The prosecutor] told me, ‘I swear that you are going to sign this document; I will get to the person who you love the most, and at that moment, you are the one who is going to call me so that I will give you the document to sign.’ And he did it,” said García Rodríguez.

“He arrested my dad and my first cousins, he placed an arrest warrant against my brother, and he persecuted my family and my children.”

García Rodríguez’s case also highlights the challenges faced by suspects being held in pretrial detention — which some estimates put as high as 40% of Mexico’s prison population — to communicate with the outside and obtain legal assistance.

“From the cell, it is impossible to maintain communication, not only with the judge or with the court itself but also with lawyers, and to have access to files,” he said. “For us, after four or five years in prison, the family’s resources ran out, and the lawyers were left with all our patrimony.”

At a hearing in January 2023, Mexican officials denied torturing Rodriguez and Alpizar, and pointed out that medical examinations did not indicate physical or mental injuries, and argued that the IACHR had ignored the State’s investigation into the torture allegations.

The case of García Rodríguez and Alpízar Ortiz, as well as others heard by the IACHR, have thrown a spotlight on pretrial detention, which is covered in Mexico’s penal code, as well as “Article 19 of the Constitution under the 2008 reforms,” according to the IACHR. Just a few months after the ruling in the García Rodríguez case, 18 of Mexico’s 31 states decided to eliminate pretrial detentions.

Last year’s court rulings have also provided fodder for López Obrador’s attacks on the Supreme Court, who he has feuded with at times.

A 2011 constitutional reform strengthened human rights protections in Mexico and gave constitutional status to international human rights laws recognized by treaties that Mexico has signed. Because of this, the Supreme Court and Congress must abide by the IACHR rulings and nullify pretrial detentions.

The Supreme Court is empowered to nullify pretrial detentions at the judiciary level by preventing prosecutors and judges from imposing the measure, but ultimately, it is Mexico’s Congress that has the responsibility to remove pretrial detentions from the Constitution. (López Obrador’s MORENA party and its allies hold a majority in Congress).

Ignoring Congress’ role in the matter, the president has focused his ire on the Supreme Court, accusing the legal body of undermining other branches of government and putting foreign interests above Mexican law.

During a press conference earlier in April, López Obrador said, “Now they want to remove pretrial detention. Suddenly, the [Supreme Court justices] became internationalists and said, ‘Although it is in our Constitution, in the resolutions of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the OAS, they say that pretrial detention should not exist,’ and as Mexico has adhered to international agreements, our Constitution is sent to the trash.”

Moreover, López Obrador’s government argues that pretrial detentions are a safety measure in a country grappling with high crime rates. Human rights defenders argue that the mechanism disproportionately affects poor people, and contributes to an already weak judiciary.

According to a 2021 National Survey of the Population Deprived of Liberty (ENPOL), nearly 60% make USD $400 or less per month, while 25% make less than $175, far less than minimum wage.

According to the World Justice Project, which analyzes the strength of justice systems globally, Mexico’s criminal justice system ranks 132nd out of 142 countries.

Léon, the lawyer and rights defender, said that pretrial detention contributes to the country’s criminal justice problems. “Our police forces are very repressive, and what many agencies continue to do … is the practice of arbitrary detentions, extortion, and the fabrication of crimes because it has been much more effective for the prosecutors to fabricate those responsible than to truly investigate. So [pretrial detention], then, upholds this complex puzzle of structural weaknesses and lack of institutional capacities in the country,” he said.

For García Rodríguez, who continues to appeal his 2022 murder conviction, the effects of pretrial detention have been more personal. “Above all, the stigma of being publicly accused of murder without being one. Well, it generated very serious damage to my family, my children, my father, and my brothers. They shattered whole lives. It threw my family into a state of social contempt,” said Rodríguez.