Military helicopters are circling over brand new barbed wire rising up at the US-Mexican border. What encounter awaits this global superpower in armed suspense? Several hundred kilometres further down, a trek of tired but determined migrants, including families, children and a new-born girl known as the first ‘caravan baby’ is slowly making its way through Mexico. Who are they, what awaits them, and why is their journey proving to be a tightrope walk for the Mexican government? We explain the quick facts.

Who are the migrants of the caravans?

Of the estimated 7,000 people that have initially joined the caravan, the group of migrants still on the road to the US is estimated at 4,000 to 5,000 people. The migrants a have been on the road for three weeks, and just arrived in Mexico City today.

Fleeing from mostly Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, some of them have covered more than 1,200 km so far – by foot, as Mexican authorities have denied providing public transport. While exact numbers are not easily confirmed, observers claim that 25% of the migrants are children, and 10% of them are unaccompanied minors.

Why are they marching and what will await them?

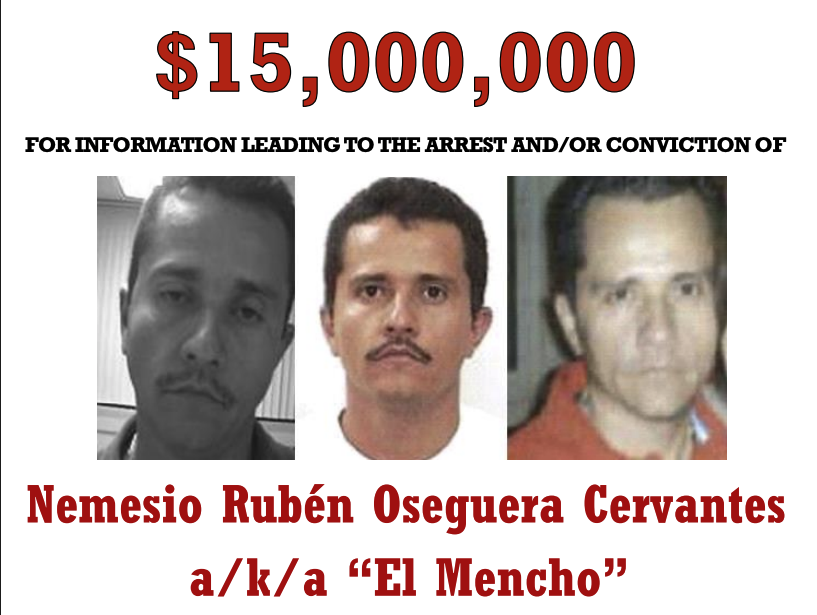

The exodus of migrants from Central America is a symptom of the precarious conditions they face in their native countries. Gang-related violence and poverty in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala adding to civil unrest and allegations of political repression in Nicaragua: Many hope to escape threats to their lifes and find for a better life in the US.

Their decision to leave behind their homes and set foot on a long and dangerous journey might have also been fueled by hopes that the tough stance towards migration of the current US administration is easing. Especially migrant families with young children may have been motivated by the news that President Donald Trump’s ‘Zero Tolerance Policy‘ on illegal border crossing was temporarily suspended for migrating parents. This announcement, made earlier this summer, was following suit after am international controversy about US policy to separate parents from their children when detaining them at the border had sparked harsh criticism in the US and abroad.

Why are they making headlines?

The sheer number of migrants certainly does not justify the tremendous international attention. To compare, 1.49 million foreign-born individuals who moved to the United States in 2016, according to migration statistics. In other words, about 4000 people, the estimated number of migrants of the caravan, entered the country every single day. Neither is the phenomena of caravans of migrants trekking by foot to the border new; in the past, several of these caravans have largely gone unnoticed. Why is this caravan suddenly making so many headlines?

The issue has little to do with the migrants themselves but boils down to the political rhetoric surrounding US President Trump, who is trying to turn the marchers into political capital for midterm elections that will be held this Tuesday. Delivering messages of fear about migrants that he frames as a security threat for the US, he is trying to pursue US voters to cast their vote for his Republican party. On Sunday, Mr Trump told his supporters at an election rally to “look at what is marching up”, calling the migrants “an invasion”.

That political symbolism has long started to rule the US response to migration might also be seen in the decision to send 5,000 Army troops to the US-Mexican border. While the forces have arrived armed, US law actually forbids them to engage in detaining anybody – meaning that they are in reality confined to assist US bborderofficials, reinforcing infrastructure or provide emergency medical care.

What is Mexico’s political response?

Mexico finds itself under pressure from conflicting demands: The US, still an important political ally of Mexico despite a rocky relationship since the last US elections, has demanded the government to ‘stop’ the migrants from reaching the border. Last week, US President Trump tweeted that Mexican soldiers were “unable or unwilling” to stop the thousands of migrants from their journey North.

On the other hand, voices at home and abroad are calling on Mexico to come to uphold its humanitarian standards and come to the assistance of what they see as a vulnerable families, torn weeks of tough marches and involving many minors.

Torn between these opposing pressures, President Nieto’s political response is zigzagging between both poles. Earlier in October, armed police forces reportedly blocked the group of migrants from continuing – but only for a few hours, and reportedly to ‘inform’ them about a new government scheme that would allow them to stay in Mexico.

“By staying in Mexico, you can get medical attention and send your children to school”, Peña Nieto stated in a video explaining the new government scheme called ‘Estás En Tu Casa’ (‘You Are At Home’), coupled with the offer of being able to access temporary employment in the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca. While numbers have reduced, the majority of the migrants of the caravan have continued their journey.

In effect, President Nieto’s policy seems to be simultaneously appearing to be seen as opposing the migrants from continuing their track to appease his growling US peers, without loosing credibility by compromising human rights at home. Calls of the group for buses or other means of public transport were met only to be quickly withdrawn, while the caravan has been slowly continued its ways through Mexican towns it often outnumbers in headcount.

The population seems divided, as a recent poll showed that about half of respondents felt that undocumented migrants from Central America should be allowed to enter and granted refuge in Mexico, whilst about 40% were against it.

With the arrival of the migrants in Mexico’s capital today as well as the US mid-term elections tomorrow, the political suspense surrounding the long trek of the migrants has reached a new high.

Landing on the front page of international media has certainly been an unexpected destination of the migrant’s journey. Being turned into political symbolism for US election campaigns might have given them a sour foretaste of what they can expect further North – and for Mexico yet another theatre stage to witness the political tightrope act of current US-Mexican relations.