In recent years, scientists have made a number of estimations surrounding the amount of sunscreen that is annually released into the ocean. Some of the most recent studies, though already dating back to 2015, suggest that between 6,000 and 14,000 tonnes of sunscreen seep into the oceans as well as, more importantly, coral reef regions each year.

Besides protecting wearers from harmful UVA and UVB rays, concern surrounds the number of ingredients within standard sunscreens such as benzophenone-3 and -4 and a list of almost ten other harmful chemicals that have been detected in coastal waters. Oxybenzone is also one of the chemicals that can be traced in the majority of non-biodegradable sunscreens, which has been scientifically linked to toxic implications for algae that lives on the coral. Once this algae is affected, it can stunt the growth of corals and also lead to bleaching.

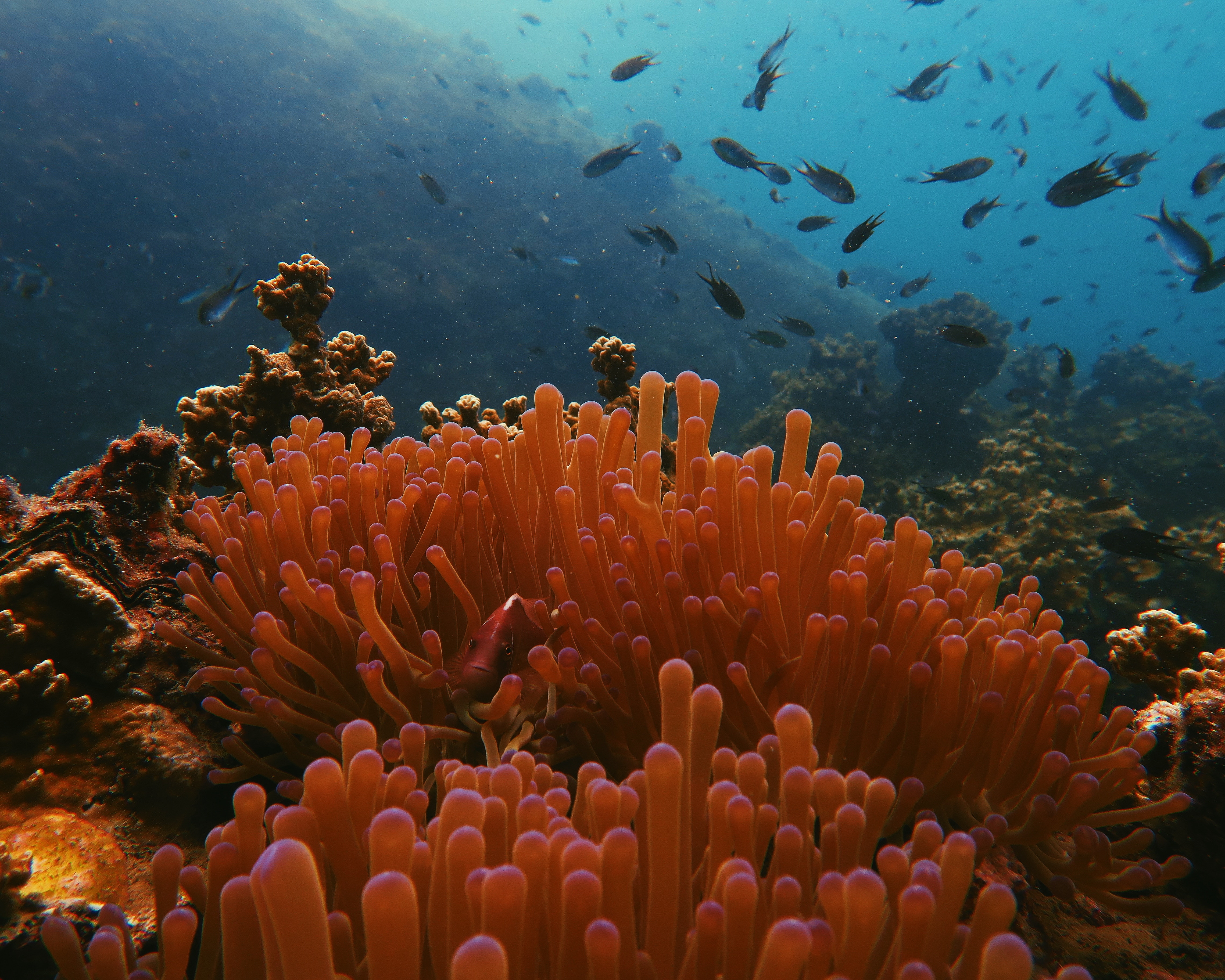

The future of coral reefs around the world hangs in the balance as the living organisms also face threats to their habitats. Increasing water temperatures, linked to climate change, affect a coral’s ability to survive, as well as threats from human intervention, pollution and careless fishing techniques. The result is wide scale coral bleaching, which can currently be seen taking over the world’s largest coral system in Australia, the Great Barrier Reef. In 2005, almost half of the coral reefs that sit off the Carribean coast of the United States were further lost to coral bleaching.

A decline in coral reefs around the globe then inadvertently affect schools of fish that rely on the reefs for their habitat and food sources, revealing a harmful cycle that plays with the future and symbiosis of many ecosystems.

Although there are certainly mixed opinions on the effects that sunscreen in the water may have upon coral reef regions, The Conversation recently explained that solid evidence regarding the subject is lacking. A number of areas around the globe are, however, beginning to tackle the contamination to seawater through sunscreen.

Just a few days ago, Key West – a city in southern Florida – became the fourth region to ban the sale of non-biodegradable sunscreens, a law anticipated to come into action in 2021. The legislation follows in the footsteps of Hawaii, the island of Palau and region of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula that have a list of restricted sunscreens. People who caught using prohibited items, reported the New York Times, could face a warning and then a fine for a second offence. In Palau, companies that are caught selling banned products risk a fine of up to US$1000.

The Mexican areas in question are located in the Riviera Maya region, a location widely popular with tourists and home to an abundance of sea life and natural attractions. Within the national park on the island of Cozumel, as well as other attractions at Chankanaab, Xcaret, Xel Ha, and Garrafon, federal legislation now requires the use of only biodegradable sunscreen. Located in Mexico’s Caribbean, the area boasts an array of coral reefs that are sought after for snorkelling and diving visits by international travellers. According to local tour groups, one recommended brand is Tropical Sands, however, they also remind visitors that if a sunscreen bottle does not state that it is biodegradable, it usually does not comply with the laws.

The effectiveness of enforcing sunscreen restrictions, however, is yet to be determined. Although regulation is in place to prevent the purchase of products that are not in line with biodegradable standards, many visitors will bring sunscreen from other locations where the rules are not enforced. Although in Mexico, visitors to some natural sites are able to swap their sunscreen for biodegradable alternatives – with as many as 100,000 bottles being exchanged at Xel-Ha annually according to the International Coral Reef Initiative – and have their own brands returned once leaving the islands, education surrounding which sunscreens are effective and the true effects chemicals have on coral reefs remains few and far between.

Others, call out the current research and suggest that in fact little is known about the true effects that sunscreen poses to coral reef systems around the world. Writing from Hawaii, the Honolulu Star made note that there is no standardised idea of what toxic sunscreens really are.