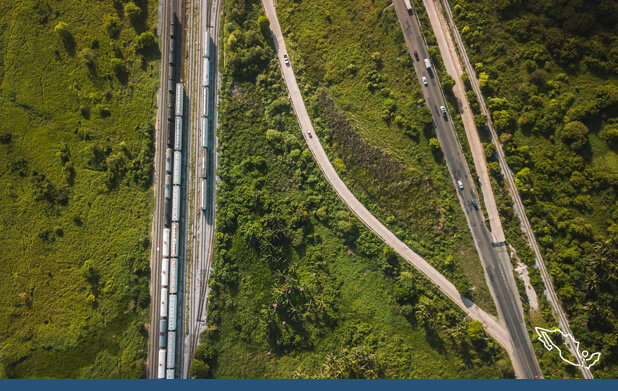

Mexico City, Mexico — A network of ports, railroads, highways and industrial parks that will stretch across Mexico’s narrow Isthmus of Tehuantepec, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans for trade, is one of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s signature mega projects. One that activists and Indigenous peoples have called a militarized undertaking to hand over the region to corporations from the United States.

Located in southeastern Mexico between the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec has been a historical point of interest for international trade because it has the narrowest stretch of land between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean — a geo-political advantage the Mexican government aims to exploit through its Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus (CIIT), a multifaceted infrastructure project that would connect the two bodies of water.

With an initial investment of around USD $440 million, the CIIT project was set to refurbish 190 miles of a railroad track while restoring the ports in Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, and Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz as well as the modernization of the international airports of Ixtepec and Minatitlán.

The corridor will also revamp highways to enable more transit.

Expecting to transport 1.4 million containers annually, the CIIT has been advertised as a cost-effective alternative to the Panama Canal.

According to the government, Oaxaca will be able to take advantage of 12 international treaties in effect with the U.S., Europe, and Asia, converting the south-southeast region into a logistics and manufacturing hub in North America.

While López Obrador has pledged sustainability and economic development for one of Mexico’s most marginalized regions, activists and community leaders have accused the president of handing over the isthmus to the interests of international investors to the detriment of the Indigenous peoples living there.

“Look, this project in itself is a violation of the rights of the Indigenous peoples, of the environment, and something that recently — with the visit of the U.S. embassies — was made clear to us, it is a threat to national sovereignty,” said Mario Quintero, the general coordinator for the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory located near the mega project in the state of Oaxaca.

For Quintero, the recent visit of special climate envoy John Kerry alongside other representatives from the U.S. government on March 21 further proves their interest and influence on López Obrador’s project, which heavily relies on foreign capital.

The development along the isthmus is not limited to the modernization of railroads and ports. The interoceanic corridor is intended as an international investment hotspot, with the government announcing last July the bidding process for 10 industrial parks, four of which will be wind power farms that López Obrador has said would be funded by the U.S. government or U.S. banks.

In addition, the Inter-American Development Bank announced it would grant between USD $1.8 billion and USD $2.8 billion in private financing for companies wishing to locate to the isthmus.

In January, Economy Minister Raquel Buenrostro, shared that a private concessionaire is expected to commit to an investment plan for each industrial park in the isthmus.

Reportedly, the Mexican government presented the logistics corridor project to the U.S. with the idea of leveraging President Joe Biden’s Chips and Science Act, a statute that aims to counteract China to produce semiconductors and bolster U.S. supply chains.

The Mexican government is looking to launch the corridor and, relying on the Chips and Science Act, allocate U.S. businesses to Mexico. “Mexico is the best place to bring companies that are now in Asia,” said Buenrostro.

Quintero fears that this planned international investment into the region will bring more harm than good, and says that the interests of the Indigenous peoples who live on the land aren’t being taken into account.

“What does this mean?” asked Quintero. “That they are going to implement extractivist projects such as mining, such as energy projects for the transfer and extraction of hydrocarbons because it is a project of very large dimensions that is being contemplated within the logic of international trade and that is not specifically contemplating the environmental, social, cultural and economic effects that it will bring to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the southeast of Mexico.”

Currently, the government is building a gas pipeline across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to supply the planned industrial parks. In addition, they also announced an investment of around USD $6 million for a liquefaction plant at the port of Salina Cruz and a coker plant to process fuel oil into gasoline.

The project’s effects on the life and territory of the region’s Indigenous peoples are already evident. For the past four years, Indigenous communities, activists, and human rights defenders have rallied against the interoceanic corridor.

For instance, in January, the Collective of Environmental Organizations of Oaxaca (COAO) denounced severe deforestation in the region due to the remodeling of the railroad, as well as damage to lagoons, forests, and marshes, reporting that to date, the government has not presented any environmental impact study for the project.

Since the beginning of the corridor in 2019, Indigenous peoples in the isthmus have organized and denounced the dispossession that the project entails and the dangers of industrializing a region while socially and economically displacing its original inhabitants.

Through roadblocks and marches, Indigenous have fought against the advancement of the inter-oceanic corridor. Construction has been halted at different points along the stretch, demanding that the authorities heed the requests of the people affected by the project.

As a response, López Obrador deployed thousands of military troops to protect the area and handed over control of the project to Mexico’s Navy in the interest of “national sovereignty.”

Security forces have since used excessive force to stop the communities’ efforts to protect their land. On more than one occasion, the Navy used violence and harassment to hamper the demonstrators’ struggle against the mega project.

Organizations such as Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (UCIZONI) have denounced state violence carried out by the Navy.

“Not only did the project come under military control, but it is using naval military force to intimidate, harass and threaten the local population,” Carlos Beas, member of UCIZONI, told Aztec Reports.

Based in Oaxaca, UCIZONI has been fighting against abuses and violations of the rights of the indigenous peoples for 40 years. Recently, the organization has seen the region become more militarized to help facilitate the construction of the mega project, according to Beas.

His own safety has come into question and in March, his organization publicly denounced threats and an alleged smear campaign that attempted to link him to organized criminal groups.”In October 2021, I received phone calls with death threats, and my home was shot twice. And then, more recently, we have also received some messages telling us that the army is going to detain us,” he explained.

Beas said his legal team has appealed to state prosecutors to disclose if the government plans to press charges against him, which at the moment remains unresolved.

“Because in Mexico, what has happened a lot under the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador is that the defenders of Indigenous rights, the defenders of the territory, the guardians of the territory, as we call them, have been murdered and persecuted, but by organized crime groups, not openly by the military or the police, as was the case before,” explained Beas.

Mexico was named the deadliest country for environmental activists in 2021 by human rights NGO Global Witness.

Oaxaca is currently the most dangerous state in Mexico for human rights defenders and activists, with 34 homicides registered from 2018 to late 2022, setting a dangerous precedent for defenders such as Beas and Quintero.

“Nowadays [violence] is through the use of the cartels that are dedicated to selling protection to companies and that operate many times in relation to the government itself,” said Beas.